RURAL FAERIE DISPATCH

February 9, 2023

Siren state

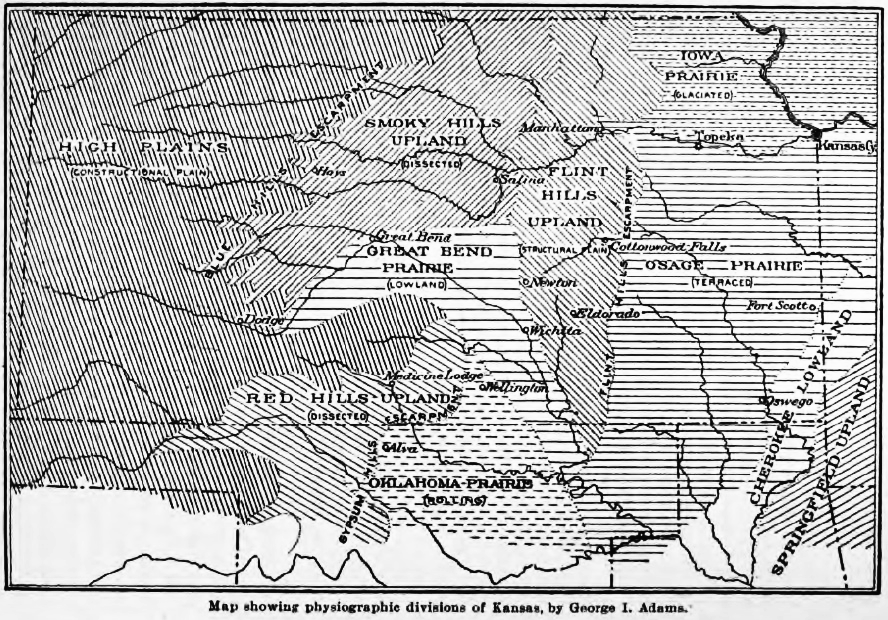

Kansas from above is a bed made well in morningtime: a square of perfectly folded linens in a dizzying palette of siennas and winter creams, a covering of mysterious patterns that may have once been indicative of aliens but that now merely signifies agriculture. Circles inside of squares, miles upon miles of shapes cut like steel in the soil. I repeat a poem to myself, a spell for safe passage, as the wind carries me into Wichita.

“Level land, dusty blacktop, and a sea of grass, and Mary.

Level land, dusty blacktop, and a sea of grass, and Mary.

Level land, dusty blacktop, and a sea of grass, and Mary.”

The next day, I stand on a platform at the bottom of our nation’s largest hand-dug well. I am alone, 109 feet below the streets of Greensburg, and eye level with rocks first designated for this task in 1887... rocks larger but perhaps* not otherwise so different from the ones that radical temperance activist Carry A. Nation wrapped in newsprint and loaded into her buggy some 45 miles and 13 years later.

On a clear day in this part of Kansas, distant towns beckon from miles away with their grain elevators and their water towers. This is the place where the wind whips and, as Mary pointed out to me, where nobody tries to drown it out. The meeting room at the arts center, the dining room at the Dixon’s, the donut shop in Plains—all silent. I have wondered briefly if this is because music might make the tornado warnings harder to hear.

But the breeze was noticeably absent on the early February afternoon that we found Carry Nation’s house unlocked. A museum now, it was filled primarily with her famed photographs. Carry in June of 1900 with her buggy full of bricks; Carry with her bible in one hand and her hatchet in the other; Kansas bar after Kansas bar, smashed.

I’m intrigued by her. In love with an alcoholic physician and Union Army veteran, she was wed at age 21 and widowed within two years—though she had already left Dr. Charles Gloyd by the time the drink had killed him. After that she cared for her newborn as well her a mother-in-law, earned a teaching certificate in Missouri, and was remarried out of necessity to a man 19 years her senior named David Nation, who moved her to Medicine Lodge.

Once there, it seems that her life’s work began. Singing hyms outside of saloons and writing letters to lawmen about the illegal sale of liquor in the county and the state, visiting prisons and helping the wives of alcoholics. It was there, in that house-turned-museum, that the lord first spoke to her. “Go to Kiowa,” he said. Break up the bars, she inferred, setting out to pick up rocks.

I wonder now whether this state—where George Washington Carver tended his small conservatory of plants and flowers, where Amelia Earhart and Moondog were born, where M.T. Liggett threw sparks, where Gordon Parks captured history, where William Least Heat-Moon mapped lifetimes, where Langston Hughes first learned to suffer in monosyllables, and where both Carry Nation and John Brown took to extremes—is silent, not in order to hear sirens, but to better hear god.